.jpg)

.jpg)

St. Paul's River residents Chesley Griffin and Roger Roberts remember “the big move.”

I remember. I remember what we call moving out. I remember moving out in the spring of the year. We would carry everything—everything, everything, everything. Whatever we had. And there was no two of anything. There was just one, you know. And the stove had to go, and everything had to go. You know what I mean. In most cases. And chairs. Dog team, too, because in the early years we had a dog team, and all of the bedclothes.

And Mum, I remember Mum's cabbage. She would always have cabbage and turnips and carrots and all those things. And she would put them up in the nose of the boat. Right, right up in what we call the cuddy. And I remember the old motorboat just shaking and jiggling, and the poor little plants doing this, you know, all the way out, all the way out. It was just, just amazing. And the cat in the bag. So, we put the cat in the bag because the cat would jump overboard, you know what I mean. And all the way out, it was just vibration all the way out. You know, it was just, it was amazing. Seriously.

We call it a flat; it's a small boat that you row to wherever we had our boats moored, right. And a lot of times they used to use that to put the [sled] dogs in. But George Nother didn't, see. George Nother had his dogs in the nose [the front] of her [the boat]. And he put his stove in the flat. And it was a little bit wavy. You see, there's always an undertow coming in there at Stick Point. He turned the point there, and the flat tipped over, and he lost his stove. I laugh at it, but it wasn't funny, you know. I laugh at what he said. "Stick Point will never freeze over this winter. The devil will have a fire in that stove all winter" That's a true story. He told me that himself.

.jpg)

In the nineteenth century, liveyeres—permanent white residents—on the Lower North Shore often maintained two homes. One was a summer house, located on a headland or an island, where inhabitants could row or sail to nearby fishing grounds. The other was a winter house, usually located on the mainland at the far end of a bay or at the mouth of a river. There, occupants were better protected from harsh coastal winds and could more easily secure fresh water, wood for cooking and heating, small and big game for sustenance, and fur-bearing animals for the fur trade.

Families or individuals moved to their summer quarters in May or June and returned to their winter quarters in September or October. Anthropologists refer to this tradition of seasonal migration as "transhumance."

In an 1858 report about St. Paul's River, Congregationalist minister Charles C. Carpenter described both summer and winter houses as "huts or tilts … small and rude, being built of timber sawn by hand and generally thatched with turf and the bark of trees."

In The Labrador Mission (1878), Samuel R. Butler, a later Congregationalist missionary in the vicinity of St. Paul's River, noted: "Some, however, have frame houses, … [which] are roomy and comfortable."

.jpg)

Eventually, marine engines and then outboard motors made it easier to travel to fish nets from the mainland. But residents of St. Paul's River continued to move to their summer houses every spring. The practice faded in the late 1970s when longliners, furnished with living quarters below deck, were introduced. Skippers and their crew could fish from the mainland or leave home for days, even weeks, at a time. They could carry all sorts of fishing gear—gill nets, trawls, lobster pots, or crab pots—and travel to wherever the fishing was best.

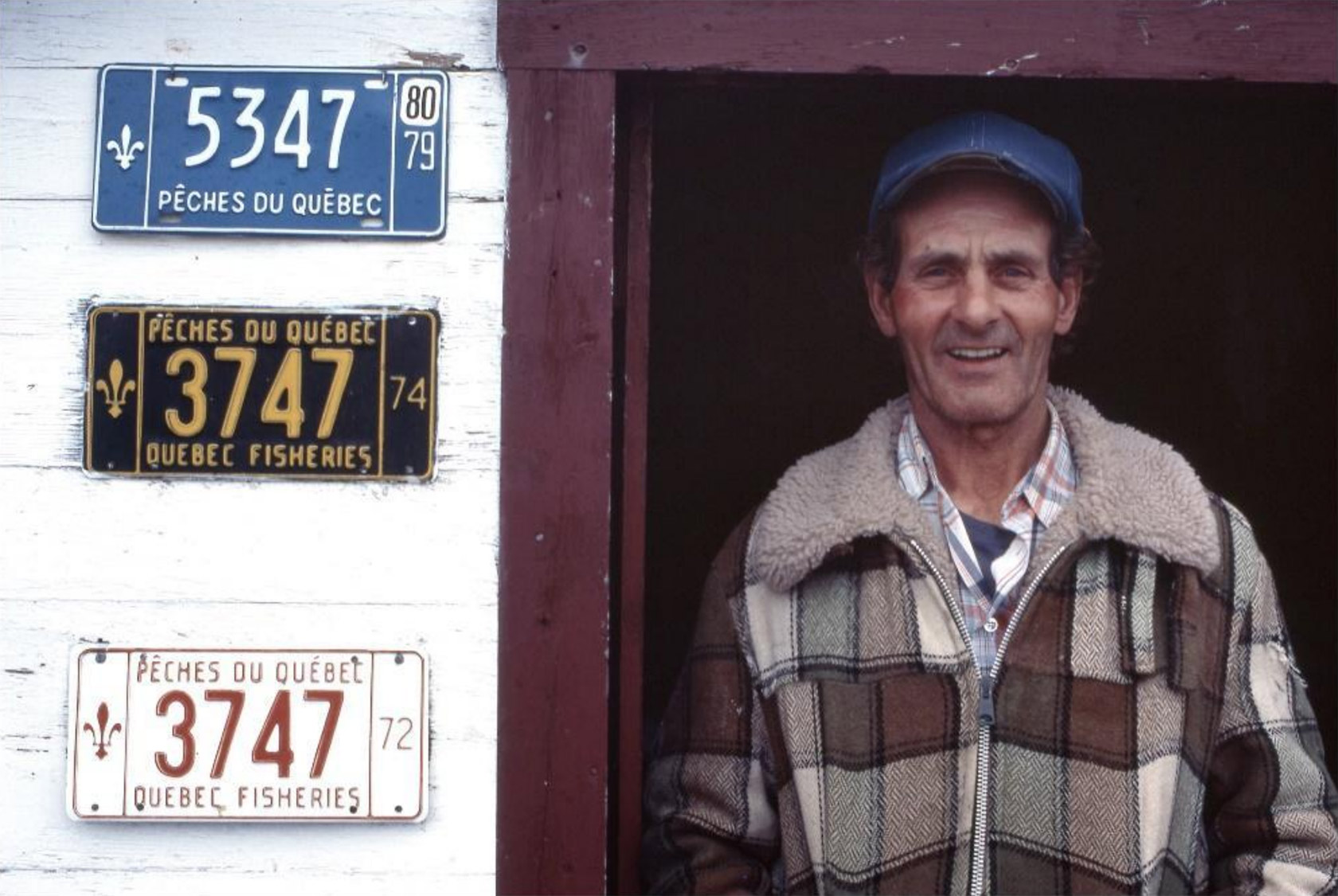

A few fishermen, such as Jack Roberts of St. Paul's River, continued to rely on an open boat and a cod trap into the early 1980s. He and his wife, Victoria, also continued to move farther out on the mainland to a site in Stick Point Bay in mid-May. In an interview with Louise Abbott in 1983, Jack explained: "You're right here, just waiting, getting ready, thinking about the fish and everything that's going to come."

_DSC5285.jpg)

Even after the fishing season ended, Jack and Victoria stayed on. "When you can't fish, you mend the nets and that," Jack said. "You always got something to do, you know." When they finally closed their summer place in September, Jack returned to St. Paul's River with reluctance. "I'd sooner be out here. The air's different from what it is in the river. It's not so stuffy—there's always a cool breeze. When I comes out here, I sleeps better, and I gets a better appetite."

Today, the annual seasonal migration is only a memory for older residents of St. Paul's River. But residents and former residents of all ages enjoy going out to traditional sites on headlands or islands for weekends or holidays. They've renovated old summer homes or replaced them with modern cottages.

_DSC5167.jpg)

_DSC5245.jpg)